Blood Clots and Travel: What You Need to Know

More than 300 million people travel on long-distance flights (generally more than four hours) each year. Blood clots, also called Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT), can be a serious risk for some long-distance travelers. Most information about blood clots and long-distance travel comes from information that has been gathered about air travel. However, anyone traveling more than four hours, whether by air, car, bus, or train, can be at risk for blood clots.

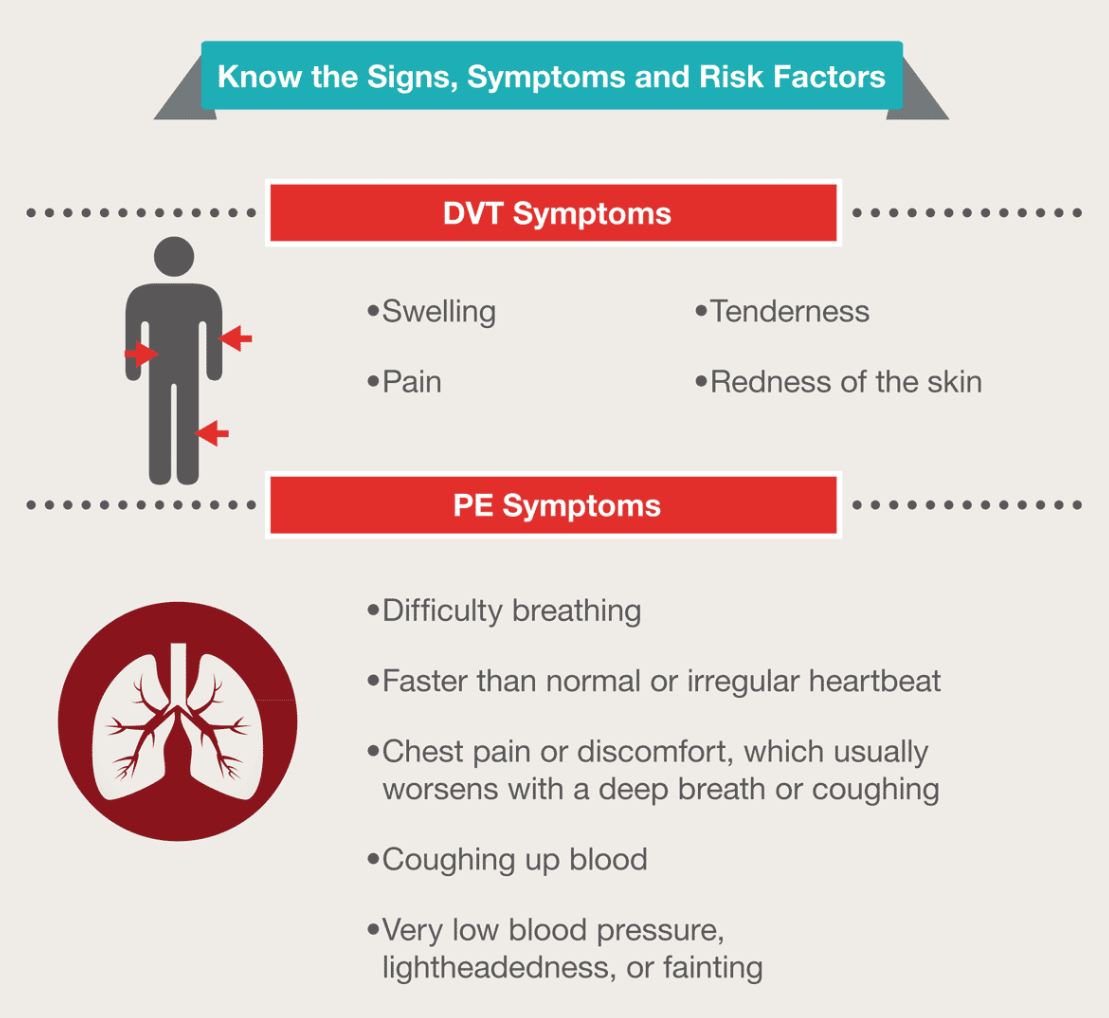

Blood clots can form in the deep veins (veins below the surface that are not visible through the skin) of your legs during travel because you are sitting still in a confined space for long periods of time. The longer you are immobile, the greater is your risk of developing a blood clot. Many times the blood clot will dissolve on its own. However, a serious health problem can occur when a part of the blood clot breaks off and travels to the lungs causing a blockage. This is called a Pulmonary Embolism (PE), and it may be fatal. The good news is there are things you can do to protect your health and reduce your risk of blood clots during a long-distance trip.

Understand What Can Increase Your Risk for Blood Clots

Even if you travel a long distance, the risk of developing a blood clot is generally very small. Your level of risk depends on the duration of travel as well as whether you have any other risks for blood clots. Most people who develop travel-associated blood clots have one or more other risks for blood clots, such as:

- Older age (risk increases after age 40)

- Obesity (body mass index [BMI] greater than 30kg/m2)

- Recent surgery or injury (within 3 months)

- Use of estrogen-containing contraceptives (for example, birth control pills, rings,patches)

- Hormone replacement therapy (medical treatment in which hormones are given to reduce the effects of menopause)

- Pregnancy and the postpartum period (up to 3 months after childbirth)

- Previous blood clot or a family history of blood clots

- Active cancer or recent cancer treatment

- Limited mobility (for example, a leg cast)

- Catheter placed in a large vein

- Varicose veins

The combination of long-distance travel with one or more of these risks may increase the likelihood of developing a blood clot. The more risks you have, the greater your chances of experiencing a blood clot. If you plan on traveling soon, talk with your doctor to learn more about what you can do to protect your health. The most important thing you can do is to learn and recognize the symptoms of blood clots.

Recognize the Symptoms

About half of people with DVT have no symptoms at all. The following are the most common symptoms of DVT that occur in the affected part of the body (usually the leg or arm):

Protect yourself and reduce your risk of blood clots during travel

- Know what to look for. Be alert to the signs and symptoms of blood clots.

- Talk with your doctor if you think you may be at risk for blood clots. If you have had a previous blood clot, or if a family member has a history of blood clots or an inherited clotting disorder, talk with your doctor to learn more about your individual risks.

- Move your legs frequently when on long trips and exercise your calf muscles to improve the flow of blood. If you’ve been sitting for a long time, take a break to stretch your legs. Extend your legs straight out and flex your ankles (pulling your toes toward you). Some airlines suggest pulling each knee up toward the chest and holding it there with your hands on your lower leg for 15 seconds, and repeat up to 10 times. These types of activities help to improve the flow of blood in your legs.

- If you are at risk, talk with your doctor to learn more about how to prevent blood clots. For example, some people may benefit by wearing graduated compression stockings.

- If you are on blood thinners, also known as anticoagulants, be sure to follow your doctor’s recommendations on medication use.

Source:

- CDC

- Gavish I, Brenner B. Air travel and the risk of thromboembolism. Intern Emerg Med 2011 Apr;6(2):113-6.

Most Commented